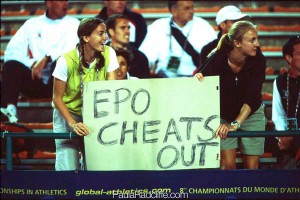

At the 2001 world championships in Edmonton, my Great Britain team-mate Hayley Tullett and I held up a sign in the stands. “EPO CHEATS OUT,” it read. Serious controversy ensued, but I had thought about it a great deal beforehand. It was the product of serious frustration.

The catalyst for the protest in Canada was the participation of the Russian athlete Olga Yegorova in a heat of the 5,000m that was about to begin near where we sat. However, the issue was much bigger than that. We were not specifically getting at her; we were making a protest at the inadequacy of drug-testing in our sport. Yegorova, who had been around for a while, was an 8min 45sec runner for 3,000m who suddenly started producing times in the 8.20s. Athletes who improve a lot can be unfairly suspected of using performance-enhancing drugs, but Yegorova’s progress was so startling that the questions were inevitable.

Shortly before Edmonton, she tested positive for the blood-boosting substance EPO, but the result was overturned because the French testing authorities did not adhere to IAAF protocol. Yegorova escaped on a technicality and was allowed to compete in the 5,000m at Edmonton, a title she went on to win.

To me and to many others, it was an example of what was wrong with our sport and why clean athletes were so frustrated with the authorities. Such a small percentage of budgets is invested in anti-doping, yet it is a vital issue. Without valid, reliable tests for certain substances, everybody knew that there was cheating going on and people getting away with it. It was seriously affecting the credibility of our sport and hurting the majority of athletes who were clean and working hard, only to lose out to those taking short cuts — or, worse still, be accused of cheating themselves.

We routinely spend our time giving drug tests, yet the system wasn’t capable of detecting the most effective and abused doping products. Finally, when somebody was caught, she got away with it because protocol had not been followed. How could clean athletes sit back and do nothing? To have accepted Yegorova’s presence without protest would have been akin to saying doping didn’t matter. To me, to have sat back and done nothing would have been not to have the courage to stand up for what I believed in; it would have given the impression that we athletes were happy with how things were, when the truth was that we weren’t.

As we held the sign up, there were Russians nearby yelling at us, and we worried about what other athletes would think of what we were doing. We knew we were taking a risk, putting ourselves up as targets for what we believed in. Yet I have always said that fear is no reason not to do what you believe is right. We felt that the IAAF wasn’t listening to us or doing enough to fight doping; we wanted the public to know that most athletes were clean and weren’t happy with the way our sport was being portrayed.

As we held the sign up, there were Russians nearby yelling at us, and we worried about what other athletes would think of what we were doing. We knew we were taking a risk, putting ourselves up as targets for what we believed in. Yet I have always said that fear is no reason not to do what you believe is right. We felt that the IAAF wasn’t listening to us or doing enough to fight doping; we wanted the public to know that most athletes were clean and weren’t happy with the way our sport was being portrayed.

Athletics is an amazing sport. It has brought so much to me as a person. To see its credibility damaged, to think about parents not wanting their children to take up athletics because of the fear of facing the spectre of drugs if they wanted to advance, hurts me. Running is about who works hardest and then runs fastest. It is about getting to the finish first fairly. Every athlete must start from the same point, something that is not possible when some are doping. If you invest so much of yourself, you have a right to fair competition and a right to be able to prove your innocence. That is one of the bugbears of modern sport: how does the successful athlete prove he or she is clean? By passing the tests? Everybody knows the tests are not guaranteed to expose the cheats. We wanted to focus attention on the need for better, more accurate testing and greater use of blood profiling tests.

I got involved in athletics because I loved it and wanted to see how good I could be. If you used drugs, how could you ever truly know this? It was also time, as athletes, to accept that we had a responsibility to our sport, too; we had to do something, and work with the authorities to do something about it.

Before the 1999 European Cup meeting in Paris, I read an article about the French 5,000m and cross-country runner Blandine Bitzner-Ducret. She raced with a red hairband around her arm. In an interview she explained that it was her protest against the lack of adequate testing in athletics and a plea for blood tests. The day before we raced at the European Cup, I spoke to her about it.

“Blandine, I think what you’re doing is right. Would you mind if I wore something like this as well?” “No,” she said. “I don’t mind at all. The more people that do it, the better.”

I thought an armband would be restrictive, so I opted instead for a red ribbon on my running vest. Not having time to get some proper red ribbon for the next day’s 5,000m, I found a red card, cut a piece from it and pinned it to the vest. Blandine was pleased to see someone else making this show of support for drug-free sport. People ask me now would I mind if they wore a red ribbon. I tell them to go right ahead. What I don’t do is preach to people and try to persuade them to make this stand. It has to come from the heart of each athlete. The red ribbon is now part of my racing uniform. It’s my small statement of what I believe in.

I believe totally in testing, in competition and especially out of competition. It is my responsibility to keep the authorities informed of my whereabouts. You let them know where you intend to be three months in advance and keep them updated about any change to your schedule that would prevent you from being at the listed address. The updates are required three days in advance. If you are not at the registered address when the testers call, it is recorded as a no-show. Three of those, and there is a case to answer. It’s strict, but unfortunately the way it has to be. I have been tested on my birthday at a restaurant in Belfast; the tester came into the loo with me, and a sample was provided.

There is a British tester who regularly comes to our home in Loughborough. She is great, very courteous, and always apologises for turning up when we’re in the middle of something. Once she came just after I had returned from a long run. It was a humid day, I had just been to the loo, and there was no way I could produce immediately. She had to wait a long time, accompany me to the bathroom while I showered, and I was saying all the time, “There’s no need to apologise — testing benefits us all.”

At other times she has had to come out at short notice after I had set a world best and needed to be tested that night. Twice in my life I have been cross and complained. Once was at a cross-country race near the beginning of my career. There were no female drug-testers available, so I had to be observed as I produced a sample by a male tester. Embarrassing and intimidating. Another time a tester showed up at our home when we weren’t there and then phoned me to say I would get a warning. I had notified the IAAF I would be away, and immediately phoned to confirm this. Unfortunately, there had been a delay in forwarding the information, but there had been no need for the tester’s rudeness.

In 2002, after a year of considerable success, I had to face the whisperings and accusations about whether or not I was clean. Even when you know the truth, that kind of talk hurts. I had worked so hard for my results, yet what more could I do? I was being tested all the time and openly putting myself out to try to get the tests more developed. At that time I asked the IAAF to refrigerate my samples because I couldn’t think of any other way to establish my innocence and my attitude to testing. In this way they can be tested in the future as more accurate tests become available.

One of those who publicly questioned me was Stéfan L’Hermitte, a sports writer with L’Equipe. He wrote that you couldn’t trust my performances and insinuated that I doped. I am quite fluent in French, but to be certain that I had fully understood the article, I asked two French friends to read it through. For them the meaning was clear: the writer did not believe I was clean.

I was so hurt and angry, I rang him at work and tackled him about his reasons for suggesting I doped, reasons he had not mentioned in his piece. He seemed to be surprised by my phone call. All he could say was that he had the right to offer his opinion. “Yes, you do,” I said, “but in private, or by saying it is your unproven opinion. Not by writing a piece that attempts to destroy someone’s reputation and credibility without putting up one bit of evidence, not one iota of proof.”

He continued to say that as a journalist he was entitled to his view. I replied that he had no right to take away somebody’s reputation without having some basis for doing so. “I’ve laid myself open to every test available and have samples frozen so tests can be conducted in the future. Do you have a suggestion about what more I can do to satisfy your doubts?” However, I can’t allow such things to get to me and stop me doing what I enjoy doing. There comes a time when you have to switch off and concentrate solely on your training and preparation. What matters is what you know about yourself, what you think about yourself and what those closest to you think of you. Of course it affects me if somebody accuses me. No matter how many times you tell yourself you don’t care what a few idiots think, it still wounds and hurts. If I wrote an article accusing a journalist of plagiarism and did not offer any evidence to support the allegation, wouldn’t that journalist be entitled to be upset? It is the same with some chat boards. I read them and am hurt by the injustice and often outright hatred of some of the posters. It shouldn’t, but of course it does still bother me. I want to discover their identity, confront that person, reasonably discuss with them why they feel that way. Of course, that is irrational. The best thing is just not go there, not to read articles I know will hurt me. Being in the public eye and up for public dissection has certainly made me a tougher person.

There is a trade-off between the amount of time and energy you can devote to making the case for drug-free sport and the danger of it becoming a distraction and harming your career. Ultimately, during the short time I have available to make the most of my career, I want nothing to interfere with the quality of my training and recuperation, because the raison d’être of the professional athlete is to be as good as he or she can be. But sometimes I get frustrated that I haven’t pushed hard enough or devoted enough time to the anti-doping issue. Once my career is over, it will become a priority.

There are times I am angry with myself for not doing more, because it is important, especially so for young people coming into the sport. Our great sport has enriched me as a person and given me self-confidence. It pains me to think parents are saying, “But what happens if my son is offered performance- enhancing drugs?” At the 2004 Athens Olympics we saw a new attitude and much more resolve from the International Olympic Committee. We are going in the right direction, but athletes and officials need to work together. There is no doubt that it will be a long, hard fight. I believe it is a battle that can be won.